The day finally came. Before this week, I had performed surgery…on a telescope; on a camera; on the treadmill, once; and on the pedicycle… well, let’s just say more than once. This week, for the first time since the mission began, Dr. Mars had to break out her tool kit and run a procedure on a living, breathing person.

Fortunately, it was only on a foot, and was a VERY minor maneuver. I won’t describe it in too much detail. When the entire population of a planet consists of six people, it’s almost impossible to maintain confidentiality. Confidentiality is part of Autonomy, one of the four major branches of medical ethics. People have the right to refuse treatment, direct their treatment, and have the details of their respective treatment(s) not disclosed to the world – any world. In this case, the patient in question kindly gave me permission to mention that the procedure in question involved debulking a wart. Using a scalpel, I removed enough layers of the wart that this person’s shoes could comfortably fit again. Many people on this planet have done as much with a pocket knife, without the assistance of a doctor. Many of these people, including my patient, have also ended up in pain and bleeding. We avoided both of these, kept things clean and cut the darn thing down to the point where topical wart treatment – the stuff you buy at the store – could start taking effect.*

You might be wondering: why on EARTH would you come to Mars with a wart in tow? The answer, of course, is that you wouldn’t. You would have it frozen off before launch, which is exactly what this person did, just a few weeks before the mission. It’s also what everyone else who has come to me with a problem in the last four months did before they came to sMars: visited their doctor; had their eyes, ears, and teeth checked; oil changed, and unwanted bits removed, warts and all, etc.

Unfortunately, when it comes to the fact that you are now 140 million miles from the nearest hospital, your physiology didn’t get the memo. Those aches and pains that bothered you once-in-a-while: they are still there when you get to Mars. In the space between Earth and Mars, the lack of gravity may ease the burden on arthritic joints and old sports injuries. At the same time, thanks to the lack of force keeping your bodily fluids in place, problems like headaches, backaches, and nasal congestion increase. What happens to your heart and your eyesight is far worse. Normally, your heart sits with its big left chamber on your diaphragm like a slightly overweight football player warming the bench. With nothing to keep its rear-end seated, your heart floats in your chest, assuming a sort of roundish shape. In this configuration, your heart isn’t as efficient as when its power units, the ventricles, are long and slender, and its tip, like the tail of a football, is pointed down towards your left hand. The eyesight problems come from too much fluid in the head, or so we think. Increased pressure in the closed volume that is your skull pushes on the eye sockets, and the eyes, and, sometimes, leads to vision loss.

Here in full gravity, and on Mars in 1/3rd gravity, we don’t worry about ballooning hearts and bulging eyes so much as we worry about slips, trips, and falls; kitchen knives; broken glass; live wires; fires; and, of course, nagging old injuries. Demographically, our group looks a lot like many astronaut pools: nerds whose definitions of fun include climbing mountains, diving oceans, and jumping out of planes. Living like supermen is super-fun and comes with a catch: you’re going to take your lumps. Elbows; knees; finger joints; hips, backs; toes; and necks – they aren’t not enough of a mess to ground us, but they’re not factory-new, either. Even if our parts were shiny as chrome, we’d still be human. Humans, even extremely fit ones, get cuts, broken bones, and infections of various kinds. We have accidents. We get burned. We sprain and strain and, yes, have skin problems, including warts.

Unlike Mars, sMars has a hospital. It’s at least an hour away. That’s enough time to make the call, prep the helicopter, fly up the mountain, land, pick up the patient, and go back…if there’s a chopper fueled, a flight team ready, and the weather is favorable. That’s a lot of ifs, so it’s in our best interest to be prepared to treat as many things as we can – especially because most problems people have a day-to-day basis don’t require a hospital or a chopper. Most are minor. For the slightly-more-than-minor situations, what’s most often required is a well-trained professional with steady hands and a bunch of supplies.

Unlike Mars, sMars has a hospital. It’s at least an hour away. That’s enough time to make the call, prep the helicopter, fly up the mountain, land, pick up the patient, and go back…if there’s a chopper fueled, a flight team ready, and the weather is favorable. That’s a lot of ifs, so it’s in our best interest to be prepared to treat as many things as we can – especially because most problems people have a day-to-day basis don’t require a hospital or a chopper. Most are minor. For the slightly-more-than-minor situations, what’s most often required is a well-trained professional with steady hands and a bunch of supplies.

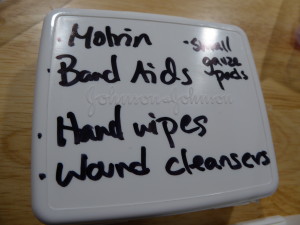

And there, dear friends, is the rub: when the drug store is more than a hundred million miles away, there’s no running out for more bandages. That’s why one of the great – if not THE great – standing question in my line of work is: What’s in your bag, Space Doc? What should you – what should I – be prepared to treat at all times?

NASA has a list of dozens of ailments that should be treatable during a long-distance foree from Earth. Using the Space Exploration Medical Condition List as a guide, I’ve gathered supplies to treat the following:

1) Allergies

2) Asthma

3) Cough and cold/sore throat

4) Fungal Infections, Topical and vaginal

5) The following disorders of the skin: Dryness, itch, inflammation, warts, dryness, and a variety of superficial gram positive and gram negative infections

6) Mild Upper Respiratory Tract Infection

7) Upper GI: Indigestion, Acid reflux

8) Lower GI: Diarrhea, Constipation; Hemorrhoids

9) Burns: 1st and 2nd degree

10) Lacerations: 1st and 2nd degree, though local anesthetic and saline flushes would be required prior to suturing

11) Various musculoskeletal injuries

12) Anaphylaxis

13) Dry eyes and lips

14) Nocturnal noise sensitivity (via earplugs)

15) Mild-moderate pain

That’s all, folks. It doesn’t look like much, but under each category are a LOT of different things. Take #11. That’s all the sprains, strains, bumps, bruises, and soreness that a group of dedicated people can conjure up. #15 covers a lot of ground as well. I can deal with all this, and a bit more, using only my two hands (gloved), a small brown bag with a few tools, and this shelf full of supplies. That’s the good news: you don’t need the hospital, or the chopper, to get basic, decent care on sMars, or, with a doctor on the crew, on Mars.

In terms of space medicine, there’s a lot of good news like that…and about as much bad news. Good news! Respiratory viruses like influenza don’t arise during a mission. For these, as well as the common cold and flu, you need a vector to bring the bug to you. That’s animals, in the case of the cold, and we don’t have any new ones coming into our mission. Flu and rhinoviruses, which transmit the common cold, can live on surfaces, but not for long. This is why people gown up when packing space payloads – so they won’t transmit anything.

Less-than-good news: humans are a constant vector for viruses like the herpes virus, which lives in our nervous system and can be transmitted by bodily fluids; HPV, which create warts; and all of the bacteria in our guts, which don’t harm the carrier under normal circumstance, but can harm others. Pathogens can also grow on food. Recently, we had mold on a few of our plants. This particular mold does not harm humans, but there are molds, spores, and fungus that can, and we can’t NOT take these with us to space. If food spoils, spores that were packaged into the food, mostly staph and bacillus, can definitely come out to play. If we culture food in space – like bread, cheese and yogurt, which we do – that can easily happen as well.

Oral-fecal transmission of gut pathogens from one crew person to another is a real concern, as well. We’re careful, and clean, and so far haven’t had an issue. Interestingly enough, we may NEVER have this particular issue going forward. Why not? Well, many in the medical community believe that at some point in the mission, most of the crew’s microbiomes – our bacterial identities – will be extremely similar. In other words, at the microbial level at least, we might start to resemble one another.

At that point, cross-contamination of one crew person’s gut bacteria into another crew person’s food wouldn’t be as an much of an issue. However, similarly itself can be a problem. In a normal human existence, our environments are constantly changing. Animals, including people, plants, and pollen, drift in and out of our days and nights, challenging us immunologically. Coming into contact with these, as well as millions of viruses, bacteria, fungi, yeasts, and helminths (worms), is normal. Similar to the way continual exercise keeps our muscles healthy, the challenges provided by these close-encounters-of-the-icky-kind may be essential to keeping our immune systems strong – individually, and collectively.

How important in a microbially diverse environment, and the subsequent immune training? To put it bluntly, we don’t yet know what the best balance is between clean and dirty. We know now for a fact that too-clean is a bad thing. Immunologically, not enough dirt (viruses, bacteria, fungi, helminths, etc) leads to over-reactions like allergies and autoimmune disease, and to immune systems that don’t know how to fight off common viruses like polio (which is everywhere humans are). On the other hand, too dirty is terrible. Filth breeds diseases like TB; influenza; measles, mumps and bumps like chickenpox (a herpes virus); as well as a staggering array of pneumonias. So, it is a balance. All of us have been thoroughly vaccinated, but we don’t have a large variety of challenging encounters, unless you count fighting off whatever’s trying to kill our bean plants. Without these encounters and challenges, we may not be able to regulate or sustain a healthy immune systems in the long run.

They are studying these issues right now on the ISS, and so are we here on sMars. In the meanwhile, I don’t worry much about communicable diseases like colds, or even GI bugs, which will make us unhappy for a while before we beat them. I DO, on the other hand, worry about accidents.

Accidents are the #1 killers of people in our age group. Trauma sustained during accidents kills people 20-40 years old in the US more than anything else does. After 40, the scale start to tip towards medical problems. For now, I think about falls, and the injuries that people can sustain when they go down. Statistically, this is most likely to occur in the hab, where we keep the sharp tools, tall ladders, and hot cooking surfaces. However, I can handle all that. What I hope not to ever handle is a major accident that takes place outside, on the lava. Out there, sMars, much like real Mars, has loose soil to slip on, sharp rocks to crack your head and your helmet, and gaping holes in the ground that, thanks to gravity, are very bad places to stumble into. That’s what keeps me up nights, if you want to know the truth: the thought that one of the crew will get hurt while on EVA; hurt so badly that I need to cut them out of their suit, put a white collar on their neck, strap them to a board, and carry them back to the habitat.

Rather than lose more than a very modest amount of sleep over the prospect, I decided to do something about it. I can’t STOP people from falling down holes that weren’t there a moment ago. This happens to us nearly every time we walk out. There’s no way around it. The lava flows are old and fragile. You’re walking along, then, CRACK, you’re falling. Fortunately, so far, when the flows crack under our weight and drop us, we haven’t gone more than a foot. To guard against the day when the ground breaks and we go down, hard, we’ve started practicing. Practicing for a medical disaster on Earth is called a drill. Our drills happen in spacesuits, so we call them medical EVAs (extravehicular activity).

True to its name, a medical EVA is an EVA dedicated to attending to a medical issue. Specifically, one in which an astronaut on EVA has been injured to the point where she or he requires assistance returning to the hab. This could be something relatively benign, like falling and dislocating a hip or knee, or something truly catastrophic, like a suit breech that results in decompression syndrome.

The worst-case-scenario is the one that we practiced first. We started on a dummy – an empty spacesuit stuffed with blankets. We discovered 2 things in rapid succession:

- Even empty suits are stupid heavy.

- Strapping a body to a flat board when that body is wearing a large helmet and a large backpack full of gear is… challenging.

A lot of padding and some creative arranging later, we get Bernie, our pretend patient, strapped to the big green evacuation board and back to the hab. When the time came to practice rescuing from rapid decompression on a real person, we took it very slowly and very cautiously. We started with the basics of CPR. We discussed how high pressure in a suit can be – must be, to keep someone alive – and what happens when that pressure rapidly vanishes. Let’s just say that the bends are the least of your worries. In the event that any one of us got hurt badly enough to need this kind of care, it would be all hands on deck, which is why the whole crew has to be medically trained to a certain level, not just me. In the event that I was the one who fell and cracked my helmet open, the whole crew would have to take care of business without their medical officer to direct them.

So we come full circle back to the question that we began with: What is Dr. Mars’ job? Bumps and bruises? Stitching cuts? On demand wart removal? Relocating limbs, plastering cracked bones, salving burns? The answer is all of the above. Above all, I feel that my job, and the job of any medical officer on a mission such as this, is to keep her eyes open and PREVENT injuries, if possible. That wart should never have threatened to take over the world. The crew member in question, and then the entire crew, was admonished to come to me EARLY and OFTEN if there’s a problem. Of course, geniuses who blast off in rockets and recreationally hurl themselves out of airplanes at 10,000 feet have a slightly skewed definition of “problem”. So, for their sakes, I need to keep my eyes and ears open, watch how people eat and how they move, how they exercise and how often, keep asking questions. I also train them all, in case of emergency, to be mini-Mars-doctors. One doc and five EMTs: that’s about the right ratio when the nearest hospital is 100 million miles away.

So we come full circle back to the question that we began with: What is Dr. Mars’ job? Bumps and bruises? Stitching cuts? On demand wart removal? Relocating limbs, plastering cracked bones, salving burns? The answer is all of the above. Above all, I feel that my job, and the job of any medical officer on a mission such as this, is to keep her eyes open and PREVENT injuries, if possible. That wart should never have threatened to take over the world. The crew member in question, and then the entire crew, was admonished to come to me EARLY and OFTEN if there’s a problem. Of course, geniuses who blast off in rockets and recreationally hurl themselves out of airplanes at 10,000 feet have a slightly skewed definition of “problem”. So, for their sakes, I need to keep my eyes and ears open, watch how people eat and how they move, how they exercise and how often, keep asking questions. I also train them all, in case of emergency, to be mini-Mars-doctors. One doc and five EMTs: that’s about the right ratio when the nearest hospital is 100 million miles away.

For the next 8 months and 10 days, I sincerely hope to be keep the cutting to a minimum. Little good can come of it out here. Operating on equipment is one thing. When you have only a bit of anesthetic, a limited number of needles, your office is your examination room and your surgical site is the 7×8 foot biology lab (true story), avoiding surgery is high on your list. When you think about it, though, even a hospital has only limited supplies, only so much space, and only so many doctors.

Even when those three are in abundant supply, there’s a problem. We discovered it rapidly when hurricane Sandy struck New Jersey. Near every doctor in at St. Joe’s in Patterson took up residence in the hospital, where there was light and hot food, where the halls were lined with our patients who had no homes to which to return. At that point, I realized why disasters can be so paralyzing: the most needed resources become rapidly tied up in a few places. If one of the crew is bad off, and I’m attending to her or him, that leaves four people to run the mission; to grow the food, see to the experiments; keep the hab running; communicate with ground control. The healthy crew would be working as hard as we did in October 2012 in post-Sandy New Jersey. As the docs at St. Joes were after a few weeks, a healthy Mars crew running on overdrive would be exhausted and in need of care; or, at least, relief. At that point, who is there to take over?

This is how many of us i t takes to lift a board with one person in a suit on it. Whether we could walk with it is a different question. Photo by Carmel Johnston.

Since stepping into the role of Dr. Mars nearly four months ago, I’ve had a very sobering realization: in the future, out there in space, if the injury is serious, that person is probably not going to make it. Technology won’t be to blame, I wager. The availability of necessary supplies might be a limiting factor, but it won’t be as insurmountable as the availability of crew to care for that injured person. These missions are small. Each person so vital that losing two individuals – the injured and the caregiver – would effectively paralyze many crews. It would depend on who was down, of course: the pilot or chief engineer vs the astrobiologist (nothing personal, Cypi). And in another way, it wouldn’t matter at all. According to NASA’s long list medical conditions, I am required to be able to treat headaches and hemorrhoids. I am not required to treat cardiogenic shock: lack of circulation due to heart failure. That is because resource-wise, space is a vast desert. On Earth, if an accident occurs in the desert, the walking wounded will make it out alive, if they are lucky. Those who can limp will be helped along, for as long as the healthy ones can offer assistance. Those that are too ill to limp will not make it out of the desert, nor will they make it in space. Space – deep space – is for the healthy people to boldly go. If they hope to return to Earth, the must remain so.

* If you ever have a wart, know this: they are actually a benign tumor of the skin, caused by the HPV virus, and are not to be underestimated. The little things are tough and stubborn. Use 12 weeks of the treatment you buy at the store, and, if that doesn’t work, see your doctor, because you have a benign tumor of the skin – which, though benign, is still a tumor that’s refusing to go away. This has been your Martian Medical Advice Moment.