What does one do after spending a year – an Earth year – simulating life on Mars?

There are short term and long term answers to this question. Some of them are obvious: go for a swim; take a shower and nap; eat a carton of strawberries all by yourself. Others, at least to me, seemed to come out of a now vastly broader left-field. Remember how to use a phone again was one. Oh, it didn’t take long, but when you haven’t dialed anything for a year, you have to remind yourself of the basic principle, the same way you do if you’re returning to operating a manual transmission after a foray into automatic shifting. Shift with a manual: Clutch-brake-gear-engine… Dial with a phone: Power-touchscreen-phone app-keypad… The same was true for using money. On sMars, the contents of your wallet were useless. Everyone already knew your identity. Your public transit passes were no good there. Even if there had been an ATM on the planet, money could NOT be exchanged for goods and services. A common joke on sMars was, “I bet you all the money in my wallet” – funny, because no one packs a wallet in their spacesuit.

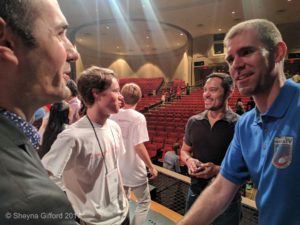

After the initial show was over, we spent a week in debrief – which is kind of like saying, I worked for a year and then went back to work. Then, two of my colleagues went back to their PhD studies. The rest of us went back to our families, at least for a while, and then resumed our lives…with a twist. Beyond getting used to trees and cars and standing in the full sunlight again, every one of us was fundamentally altered. We now carry with us a strange sort of glow: a reflected light from having walked out among the stars, or tried to, in some small way. So on top of time spent with friends and family, pets and pet projects, each of us has piled on a healthy dose of making the rounds to meet our fellow humans. We’ve been on TV shows and podcasts; presented at conferences; shaken hundreds of hands (used lots of Purell); and generally made ourselves accessible to the people of Earth. Whatever else we do with our lives, this is our job now that the mission is over: to be here for you now, and for as long as you need us to be.

There’s more than duty to that statement – there’s symmetry and a profound sense of that which underlies every true scientific endeavor. I’m speaking, of course, of humanity itself. Science is the branch of humanity dedicated to discovery, exploration, and inquiry for the purposes of self-improvement. Accruing knowledge make our lives better. Sometimes it allows us to do so in a practical way: to cure diseases, increase efficiency in industry, grow more and healthier food, and so on. Science also allows us to think and plan appropriately for our future: to make sounder fundamental choices about how and where to live, to work, to farm, and so on. Sometimes, the insights gained through our inquiries are a window into understanding ourselves and our Universe – and by understanding, to be able to make sense of our experiences, to find peace within and without, and to feel a part of our environment. To put it another way, science transforms our role in the cosmos, individually and collectively, from that of a clueless dinner party guest to that of a full-fledged family-member. By knowing who and why we are, we gain the skills to relate to and with whoever and whatever else may be out there. For all these reasons – practical and philosophical – science exerts itself every day; fights for funding, proceeds cautiously, takes pride in the benefits it provides to society, mourns and strive to learn from its mistakes. Science is you, and it’s also here for you. So it is for your sake as much as anything else that we six went and returned.

There’s more than duty to that statement – there’s symmetry and a profound sense of that which underlies every true scientific endeavor. I’m speaking, of course, of humanity itself. Science is the branch of humanity dedicated to discovery, exploration, and inquiry for the purposes of self-improvement. Accruing knowledge make our lives better. Sometimes it allows us to do so in a practical way: to cure diseases, increase efficiency in industry, grow more and healthier food, and so on. Science also allows us to think and plan appropriately for our future: to make sounder fundamental choices about how and where to live, to work, to farm, and so on. Sometimes, the insights gained through our inquiries are a window into understanding ourselves and our Universe – and by understanding, to be able to make sense of our experiences, to find peace within and without, and to feel a part of our environment. To put it another way, science transforms our role in the cosmos, individually and collectively, from that of a clueless dinner party guest to that of a full-fledged family-member. By knowing who and why we are, we gain the skills to relate to and with whoever and whatever else may be out there. For all these reasons – practical and philosophical – science exerts itself every day; fights for funding, proceeds cautiously, takes pride in the benefits it provides to society, mourns and strive to learn from its mistakes. Science is you, and it’s also here for you. So it is for your sake as much as anything else that we six went and returned.

Now that we have returned, we are marked as delegates from space to the human race. I can’t speak for my crewmates, but for my own part, this designation may be the best thing that’s ever happened to me. As anyone can tell, I love science. I love talking about science. I love teaching science. As someone who dedicated an entire year of my life entirely to science, I feel at ease admitting that science is the beginning of the wisdom, not the end. Science itself can take us light-years, the love of science itself can only take us so far. What underlies the love of science is the motivation to make the world a better place, to elevate everyone and everything, to vouchsafe and protect our civilization today and ensure a more peaceful, equitable tomorrow. That ideal is what makes Star Trek so believable – and like-able – as a version of our future selves. It’s why the US once dedicated 5.3% of our GDP to getting ourselves into space and back safely. As much as history may remember it that we, we didn’t go to just space just to spite the Russians. Then-President Kennedy asked the Soviet Union to go there with us: “to join us in developing a weather prediction program, in a new communications satellite program, and in preparation for probing the distant planets of Mars and Venus, probes which may someday unlock the deepest secrets of the Universe.” We were meant to get there together for everyone’s sake, not alone in service to our own glory.

At the Johnson Space Center, Houston, giving a lecture on the past, present and future of space simulation. 2/9/2017.

We space ambassadors are here to stay and to say that together we can do this – life on Mars, life on Earth, life anywhere humanity bands together to reach. Now that we’re back, we’re doing our best to reach as many of you as we can. To that end, we need your help. So that we can do our jobs and give you, the people of Earth, to whom we have a lasting duty and privilege of serving, the best service possible, please leave requests in the comments section below. What can we do for you? Books? Blogs? Podcasts? Bear in mind with your requests that the space simulation community is of a finite size. We are, however, very dedicated. We’ve given our lives for space travel – and most, if not all of us, would do it again in a heartbeat.